Centenary of Tanks: Crompton’s and McAfee’s Vehicles

In February 1915, a group of British engineers and naval officers worked on the development of a new and highly experimental combat vehicle, which eventually became the wonder weapon of World War I. They formed the Landships Committee at the Royal Admiralty. There, many inventions were explored and prototyped, but were ultimately deemed unusable. They were incredible on paper, but impractical to use in combat.

Amongst the many experimental ideas, several projects got “stuck” on the very verge of success. Examples of such projects include those by experienced inventor Colonel Rookes Crompton and Lieutenant Robert Macfie, a young and talented officer in the Royal Naval Air Service.

Their vehicles actually resembled tanks of the future. Unfortunately, their inventions were not meant to be. Crompton was simply unlucky, whereas Macfie’s vehicle became the subject of a scandal.

Crompton’s Workshop

The chairman of the Landships Committee, Eustace d’Eyncourt, did not mince words when evaluating Crompton’s engineering work. He once said of Crompton: “He has never presented finished projects that would work.” However, this was only a half-truth that made Crompton look bad. Crompton was actually one of the most talented engineers of his time. This is what he created over five months.

The rotating turrets, forward-facing machinegun, and front drive wheels of Crompton’s and Macfie’s vehicles found their place in future tanks

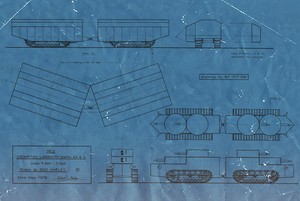

On 20 March, 1915, Crompton presented to the Landships Committee a vehicle that shared its name with the first tank—Mark I. It was a 12m long carriage with side compartments, meant for transporting infantry. The vehicle was to be driven using Bramah Joseph Diplock’s so-called “pedrail” wheels. This is not a mistake: one pedrail was used instead of two tracks. Crompton decided to use one wide band that was to run beneath the vehicle. The Landships Committee approved the project and intended to order 12 prototype models.

Meanwhile, members of the Landships Committee made a trip to the front lines in France. The Command did not allow the “naval” guests near the front lines. However, Crompton saw enough – specifically, the terrain several miles from the front – to realise that his vehicle would not be able to drive across such terrain.

Like a magician who performs the trick with the saw and box, Crompton cut his vehicle into two pieces and put them together with joint, resulting in a variant called the Mark II. Crompton decided that a “broken” vehicle would overcome shell craters much easier. He also replaced Diplock’s suspension system with more practical tracks. Everything seemed to be ready for the production of prototypes, but alas, the situation changed.

The Landships Committee demanded changes. Instead of an armoured transport for infantry, Crompton was to develop a combat vehicle. This is how the Mark III saw the light of day. It was notable for its rotating turrets and machineguns in the frontal glacis. This vehicle had the features of a tank, as it was. The inventor finished his work on the third model on 1 July, 1915. Unfortunately, the joint between the two sections remained, resulting in what was quite literally the weak link of this vehicle.

Two months later, two misfortunes befell Crompton: his son was wounded at the front and the Committee informed the colonel that his project was to be discontinued. Crompton offered hisservicesinotherfields, buthe was unsuccessful in his attempts at persuasion.

Perhaps it was a waste. Crompton’s engineering solutions were interesting. Who knows what he would have created if he had had more time?

From Workshop to Court

The Landships Committee came through several scandals. Lieutenant Robert Macfie of the Royal Naval Air Service became the focal point of one such scandal. As an inventor, he was fond of tracked vehicles, and he was one of those who brought his project to the first meeting of the Committee.

He missed the following meetings, but still received 700 British pounds for his project from the commander of the armoured division of the Royal Naval Air Service. In 1915, 700 pounds was a rather significant sum of money. Macfie had intended to spend the funds on mounting tracks on an old 5-ton truck of the Alldays company. The lieutenant shared his idea with another inventor, Murray Sueter, who helped the young enthusiast find a production base at a small company called “Nesfield and Mackenzie”. This is where everything started.

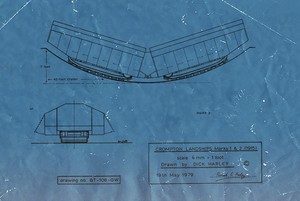

Macfie got down to work with enthusiasm but the company’s head, Albert Nesfield, disliked him. Nesfield wrote to high-ranking officials demanding that Macfie be sent away or replaced by someone else. At the same time, Nesfield began working on his own vehicle with two pairs of tracks, of which the front tracks were for steering the vehicle.

Nesfield made several miniature models and presented them to the Landships Committee on 1 July, 1915. An angry Macfie broke into the meeting and accused Nesfield of stealing his work. This resulted in a legal battle.

It was difficult to determine who was right. Nesfield had actually attempted to patent his project without knowledge of Macfie, who in turn abused his position and kept all materials to himself.

Judging from the preserved documents, there were differences between the prototypes that each person had designed. For example, Macfie’s vehicle had its steering wheel at the rear end of the vehicle. There was also one more significant feature of note. These two inventors were the first to mount the driving wheels and tracks at the front of the vehicle to increase its crossing capacity.

The Macfie–Nesfield vehicle was not designed to mount heavy armament; the vehicle only featured holes through which small arms could be fired.

This vehicle, more than other vehicles the Committee had seen thus far, resembled future British armored vehicles. Despite the ongoing conflict between them, Macfie and Nesfield advanced their design further than other engineers over six weeks. Perhaps if circumstances had been different, the heads of the Committee would have allowed them to continue their work, but they did not want to have anything to do with the Macfie-Nesfield scandal. Both inventors received 500 British pounds for their work, and the project was discontinued.

In the summer of 1915, the conservative military command evaluated the activity of the Landships Committee with great skepticism. For example, the commander of the Mediterranean Expeditionary Force, Ian Hamilton, said, “This trench war does not require much technical knowledge. High morale and healthy stomach are the most important”. These words did make sense to inventors. It rendered them unable to develop the right design to fit the war’s needs, and it made them feel like they had wasted time and money.

As the Landships Committee looked for a solution to this matter, armoured cars appeared on the battlefield. For some time, it seemed that tanks were not needed, because armoured cars were sufficient. That assumption would, with time, be proven incorrect.

Text by: Yuri Bahurin

Sources:

- Fedoseev S. Tanks of World War I. M, 2012.

- Fletcher D. The British tanks 1915-19. Ramsbury, 2001.

- Glanfield J. The Devil’s Chariots. Osprey, 2013.

- Pedersen B. A. What kept the Tank from Being the Decisive Weapon of World War One? Thesis for the degree of Master of Military Art and Science. Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, 2007.